ENGLISH VERSION DOWN BELOW

Si dice che l’aperitivo universitario sia una tradizione, qui a Padova: un’occasione informale di ritrovo, dialogo e confronto. Certamente lo sanno bene gli organizzatori dell’Aperitivo con Gaia, missione spaziale dell’ESA che sta gettando luce sulle meraviglie della nostra Galassia.

Durante l’evento divulgativo, tenutosi lo scorso 13 ottobre in un’atmosfera di convivialità al Museo dell’Osservatorio La Specola, sono intervenuti Antonella Vallenari, co-responsabile del consorzio Gaia, Michele Trabucchi, ricercatore presso l’università di Padova e leader di uno dei gruppi di ricerca di Gaia, e Paola Sartoretti, astronoma padovana all’Osservatorio di Parigi–Meudon, in carica di uno dei più rilevanti gruppi di lavoro nel consorzio Gaia.

Gaia è stata lanciata nel 2013 con l’obiettivo principale di realizzare una mappa multidimensionale della Via Lattea, studiando la composizione, il moto e l’evoluzione delle stelle. In questi dieci anni di attività, Gaia è andata ben oltre le aspettative iniziali degli stessi ricercatori che vi hanno lavorato: nell’ultima Data Release del 10 ottobre 2023 Gaia ci ha fornito un catalogo di due miliardi di stelle! E non solo: ha infatti rilevato centinaia di lenti gravitazionali, tenuto traccia di 150mila asteroidi del Sistema Solare, esplorato in profondità ammassi stellari finora irraggiungibili con qualsiasi strumento.

Gaia, che ha preso il testimone del satellite Hipparcos, si trova a 1.5 milioni di km dalla Terra, circa cinque volte la distanza Terra-Luna, in quello che è definito Punto Lagrangiano L2: questo punto di osservazione è particolarmente favorevole per lo studio del cielo profondo, in quanto la Terra è sempre frapposta tra il satellite e il Sole, in modo da “oscurare” la nostra stella e impedire disturbi nelle rilevazioni. Inoltre, in queste particolari regioni dell’orbita attorno al Sole si ha una condizione di equilibrio per i corpi, il che rende più facile e stabile il puntamento delle apparecchiature.

Ma come funziona esattamente? Il principio su cui si basa Gaia è il fenomeno fisico dell’assorbimento e dell’emissione di radiazione da parte degli atomi. Se prendiamo un fascio di luce bianca, nel momento in cui questa viene rifratta da un prisma, vediamo che si scompone nei vari colori (l’arcobaleno) in modo continuo: dal rosso passiamo all’arancio, poi al giallo etc. L’arcobaleno che vediamo ha un nome scientifico: si chiama “spettro” ed è, tecnicamente, l’insieme di tutte le frequenze in cui la luce è stata scomposta. Se ora ripetiamo la stessa esperienza sostituendo al prisma un gas rarefatto, non otterremo una figura identica: noteremo che nell’arcobaleno si sono formate delle bande nere (in questo caso si dice che lo spettro è discreto, perché appunto contiene delle discontinuità). A cosa è dovuto questo fenomeno? Chi ha cancellato delle bande dai nostri spettri continui? Il responsabile va cercato negli atomi che compongono il gas stesso: questi, a seconda dell’elemento, assorbono frequenze di luce caratteristiche. Insomma, all’idrogeno corrispondono certe bande, all’elio altre e così via.

Ad esempio, riuscite a trovare gli elementi contenuti nello strato più esterno di questa “stella misteriosa”?

Ebbene, questa è una gran bella notizia per gli astronomi: le atmosfere stellari (cioè le regioni più esterne degli astri) sono composte proprio da gas rarefatti. Dunque, misurando gli spettri di assorbimento per ogni stella, si riesce a capire da quali elementi sia composta la sua atmosfera.

Gaia fa questo grazie a uno strumento chiamato spettrografo (o spettrometro) in grado di raccogliere la bellezza di 15 milioni di spettri ogni giorno! È riuscita così a raccogliere le composizioni di oltre due miliardi di stelle, circa il doppio del numero per cui era stata progettata un decennio fa.

Gli spettri non ci forniscono però dati solo sulla composizione delle stelle: ci permettono di misurarne anche la velocità radiale (cioè la componente della velocità nella nostra direzione, quella che “punta verso di noi”). Com’è possibile ricavare una misura di velocità, che sembra così meccanica, da una misura di fatto elettromagnetica?

Si sfrutta il ben noto effetto Doppler: lo stesso principio per cui, quando siamo per strada e sentiamo un’ambulanza o un’auto della polizia che si avvicina a sirene spiegate, percepiamo il suono aumentare in frequenza sempre più, mentre quando il veicolo si allontana sentiamo un suono diverso, che diminuisce gradualmente in frequenza. Anche la luce è un’onda, anche se, a differenza del suono, non ha bisogno di un mezzo per propagarsi: dunque anche la luce può subire effetto Doppler. Noi, che riceviamo la radiazione, misuriamo una frequenza maggiore rispetto a quella emessa se la sorgente, cioè la stella, si sta avvicinando; minore se la stella si allontana. Quindi, se negli spettri vediamo delle bande di assorbimento leggermente spostate rispetto a dove si troverebbero normalmente, significa che quella sorgente, la nostra stella, è in moto. Infatti uno spostamento nelle bande indica una diversa frequenza rilevata (effetto Doppler): questa frequenza sarà tanto più diversa da quella “standard” quanto maggiore è la velocità radiale della stella.

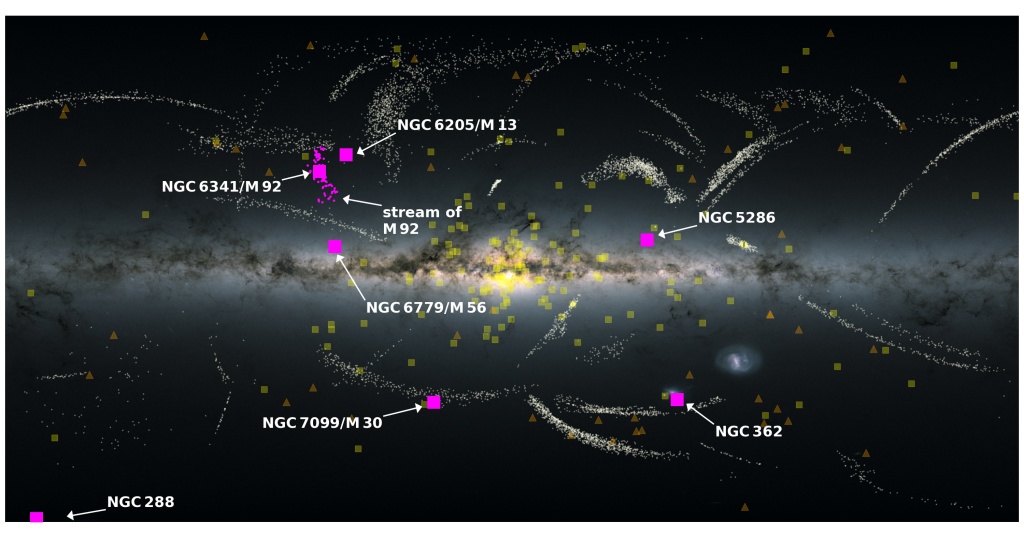

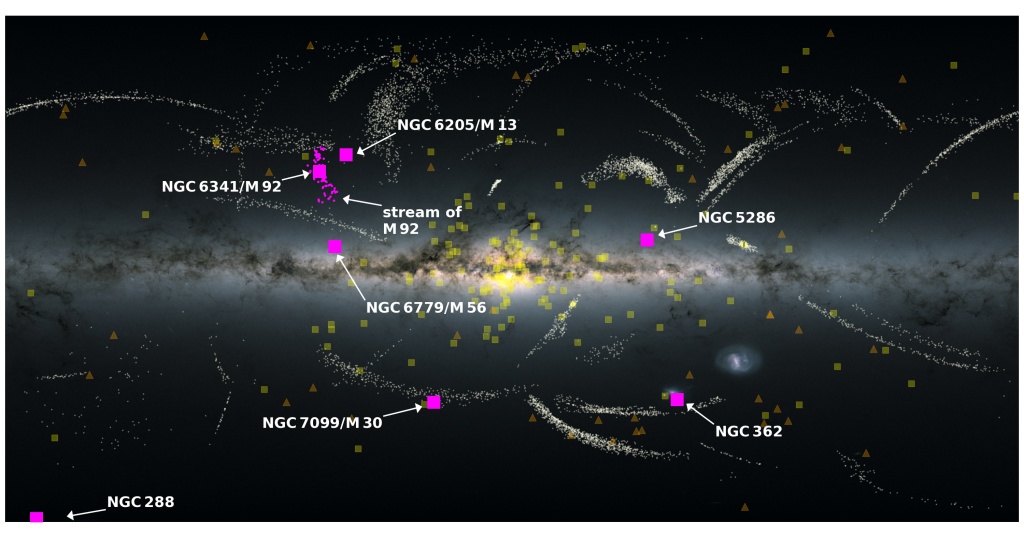

Fin qui, solo teoria. Ma le informazioni combinate su composizione chimica e velocità delle stelle hanno permesso a Gaia di fare scoperte molto importanti. Per esempio, si è compreso ancora meglio che la Via Lattea non è omogenea, né si è formata tutta in una volta: contiene infatti al suo interno dei gruppi di stelle composte da elementi chimici diversi e che si muovono in direzioni non concordi con la rotazione del corpo centrale. Ciò significa che si tratta di ex-galassie che si sono fuse con la nostra miliardi di anni fa, e le cui stelle e nubi di polvere sono state catturate dall’attrazione gravitazionale della Via Lattea.

Questi oggetti, noti nella comunità degli astronomi come stellar streams, ci forniscono non solo la prova di una Galassia-collage, ma ci rendono anche in grado di studiare la distribuzione della materia oscura intorno alla Via Lattea. La materia oscura si chiama così proprio perché non è soggetta, né tantomeno emette, la radiazione elettromagnetica (è invisibile con qualsiasi strumento ottico); tuttavia influenza gravitazionalmente i corpi che le passano vicino. Ad esempio è noto da ormai molti decenni che le stelle alla periferia delle galassie hanno una velocità troppo alta rispetto a quelle che ruotano vicino al centro: l’ipotesi finora dominante (ma non l’unica) è che questo sia dovuto a una “massa aggiuntiva” che esercita una forza e quindi causa un’accelerazione maggiore: appunto, la materia oscura. I dati e i modelli di Gaia potrebbero dirci se effettivamente c’è della materia che non vediamo nell’Universo o se dobbiamo cercare la risposta a queste anomalie da un’altra parte.

Il paziente lettore potrebbe chiedersi quale sia la lezione più importante da trarre dopo tutto questo spiegone di fisica. Ebbene, c’è un aspetto di Gaia che la rende ancora più speciale: Gaia è una missione tutta europea.

E questo ci insegna che l’Europa può, e deve, investire e continuare ad essere un faro nella ricerca scientifica, promuovendone il messaggio di pace e collaborazione tra i popoli.

ENGLISH VERSION

It is said that the university “aperitivo” (aperitif) is a tradition here in Padua: an informal occasion for gathering, dialogue and discussion. Certainly the organizers of “Aperitivo con Gaia“, an ESA space mission that is shedding light on the wonders of our Galaxy, know this well.

During the educational event, held last October 13 in a convivial atmosphere at the La Specola Observatory Museum, speakers included Antonella Vallenari, co-head of the Gaia consortium; Michele Trabucchi, a researcher at the University of Padua and leader of one of Gaia’s research groups; and Paola Sartoretti, a Paduan astronomer at the Paris-Meudon Observatory, in charge of one of the most relevant working groups in the Gaia consortium.

Gaia was launched in 2013 with the main goal of making a multidimensional map of the Milky Way by studying the composition, motion and evolution of stars. In these ten years of operation, Gaia has gone far beyond the initial expectations of the same researchers who worked on it: in the last Data Release of October 10 2023, Gaia provided us with a catalog of no less than two billion stars! And not only that: it has in fact detected hundreds of gravitational lenses, kept track of 150 thousand asteroids in the Solar System, explored in depth star clusters that up until now were unreachable by any instrument.

Gaia, which took the place of the Hipparcos satellite, is located 1.5 million km from Earth, about five times the Earth-Moon distance, at what is called the Lagrangian Point L2: this observation point is particularly favorable for studying the deep sky, as the Earth is always sandwiched between the satellite and the Sun, which is useful to “obscure” our star and avoid any disturbances during data collection. In addition, in these particular locations of the Solar orbit there is an equilibrium condition for the astronomical objects, which makes equipment pointing easier and more stable.

But how exactly does it work? Gaia’s operation is based on the physical phenomenon of absorption and emission of radiation by atoms. If white light is refracted by a prism, we will see that it decomposes into the various colors of the rainbow, in a continuous way: from red we go to orange, then to yellow etc. The rainbow we see has a scientific name: it’s called a “spectrum” and it’s, technically, the set of all the frequencies into which light has been broken down. If we now repeat the same experience by substituting a rarefied gas for the prism, we will not get an identical figure: we will notice that black bands have formed in the rainbow (in this case the spectrum is said to be discrete, because it precisely contains discontinuities). What is this phenomenon due to? What has erased bands from our continuous spectra? The reason must be sought in the atoms that make up the gas: these, depending on the element, absorb specific frequencies of light. In short, hydrogen corresponds to certain bands, helium to others, and so on.

Well, this is great news for astronomers: stellar atmospheres (i.e., the outermost regions of the stars) are composed precisely of rarefied gases. That means that, by measuring the absorption spectra for each star, we can figure out what elements its atmosphere is composed of.

Gaia does this thanks to an instrument called a spectrograph (or spectrometer) capable of collecting up to 15 million spectra every day! In this way it was able to collect the compositions of more than two billion stars, about twice the number for which it was designed for a decade ago.

However, spectra not only provide us with data on the composition of stars: they also allow us to measure their radial velocity (i.e., the component of the velocity in our direction, the one that “points toward us”). How is it possible to derive a velocity measurement, which seems so mechanical, from a measurement that is in fact electromagnetic?

It takes advantage of the well-known Doppler effect: when we are on the street and hear an ambulance or police car approaching with sirens turned on, we hear the sound increase in frequency more and more, while if the vehicle moves away we hear the sound fade, which corresponds to the fact that it decreases in frequency. Light is also a wave, although, unlike sound, it does not need a medium to propagate: therefore light is also affected by the Doppler effect. We, who receive the radiation, measure a higher frequency than that emitted if the source (in our case the star) is approaching; lower if the star is receding. So if we see absorption bands in the spectra that are slightly shifted from where they would normally be, it means that the star is in motion. In fact, a shift in the bands indicates a different detected frequency (Doppler effect): this frequency will be the more different from the “standard” frequency the greater the radial velocity of the star.

So far, just theory. But the combined information about the chemical composition and velocity of stars allowed Gaia to make very important discoveries. For example, it became more clear that the Milky Way is not homogeneous, nor did it form all at once: in fact, it contains groups of stars composed of different chemical elements and moving in different directions from the rotation of the central body. This means that these are former-galaxies that merged with ours billions of years ago, and whose stars and dust clouds were captured by the gravitational pull of the Milky Way.

These objects, known in the astronomy community as “stellar streams”, not only provide us with evidence of a sort of Galaxy-collage, but also allow us to study the distribution of dark matter around the Milky Way. The name “dark matter” comes exactly from the fact that it is not subject to the electromagnetic radiation, which means it’s invisible to any optical instrument; however, it gravitationally influences bodies nearby. For example, it has been known for many decades now that stars on the periphery of galaxies have too high a velocity compared to those rotating near the center: the dominant hypothesis so far (but not the only one) is that this is due to an “additional mass” that exerts a force and thus causes a greater acceleration: this is the effect of dark matter. Gaia data and models could tell us whether there is indeed matter we do not see in the Universe or whether we need to look elsewhere for the answer to these anomalies.

The patient reader may wonder what is the most important lesson to be learned after all this physics explanation. Well, there is one aspect of Gaia that makes it even more special: it’s an all-European mission.

And this can teach us that Europe can, and must, invest and continue to be a beacon in scientific research, promoting its message of peace and collaboration among peoples.